Check Out My Brooklyn! – A Great New Film About Gentrification

The NESRI housing team is excited about an excellent new documentary on gentrification. And, it’s not just us. The audience members at screenings, and the students in classrooms we have spoken with about the film, have been really engaged and think the film is a big hit!

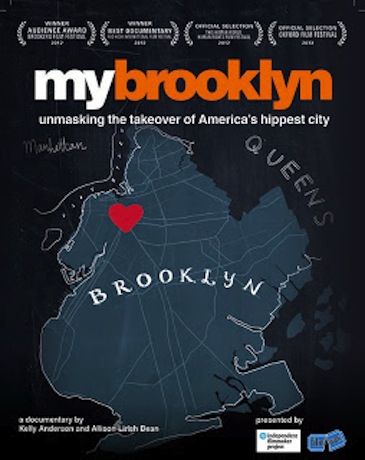

The film closely follows the changes that a rezoning plan in downtown Brooklyn, New York, creates. It captures what has become a virtually universal approach to the redevelopment of our cities and the gentrification that long-rooted communities in these cities have been confronting and are continuing to challenge. My Brooklyn, directed by Kelly Anderson and produced by Allison Lirish Dean, unveils many of the complex dynamics surrounding the City of New York’s Fulton Mall redevelopment project. It deals head-on with the palpable issues of class and race that define the project and the privilege and perceptions that have justified it. And it does this while revealing just how public policy has been, and continues to be, far from a neutral construct designed to ensure the equal and just treatment of all.

The film features the voices and in-depth knowledge of some of NESRI’s allies, including the Brooklyn-based community group, FUREE (Families United for Racial and Economic Equality) and Professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College and the Graduate Center, City University of New York, Tom Angotti – one of our housing program advisory board members.

NESRI’s housing team had the opportunity to speak with Kelly Anderson about the film. Snippets of our conversation follow – be warned: there are spoilers!

NESRI: The way the city frames the Downtown Brooklyn redevelopment project is depicted in the film. Can you tell us what you’ve witnessed change over the course of the project in how the city talks about it?

KELLY: I think the city’s gotten smarter. Joe Chan [at the time President of the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership] is basically a PR [public relations] guy. And, Purmina [Kapur, Director of the Brooklyn Office of] City Planning – her job is to put a face on policies no one wants. They’re really smart in the way they talk about it… If you look at the old literature and plans for Fulton Mall, they used to say it has “an image problem,” and things like that, but they don’t talk about it that way anymore. Now they say things like we need more “retail diversity”.

What I find really interesting is how many people – not everybody, but White people in particular – go to the idea of crime anytime you talk about gentrification. It’s amazing to me. As soon as something goes on a blog or website about the film, all of a sudden all these folks will come out and say, “Yeah, well, would you prefer it be crack-infested and crime-ridden like it was before?” As if those are the only options! So, to me it was really important to actually talk about the history of disinvestment in the film and show how a neighborhood like Fort Greene or Bedstuy got devastated by policy. That gives some context for why there was crime, as well as the pulling out of resources from that area.

[Note: Kelly Anderson is White, and has interesting things to say in relation to her location (physically and metaphorically) in her Brooklyn!]

NESRI: What did you learn in the process of making the film, about who is benefiting and who is being negatively affected by the gentrification of Brooklyn? What was your sense of how race and class interacted and how it didn’t?

KELLY: It’s interesting to me that when people see film they want to cut race out of the equation because there’s a real desire to just put it down to economics. Which is true: fundamentally, a small number of people are making a ton of money from this land use. But, in addition to that, they’re using race. Redlining is such an obvious historical example of that, and they’re still achieving the same thing, even though they are subtler about it now. I felt it was important to constantly keep reminding ourselves of that – not let people get comfortable with the idea that it was just one or the other [race or class]… That’s why I really wanted that farmers market section in there with those White residents saying that racist stuff, because the argument ultimately is kind of economic – these people passed the plan, they made a ton of money, they took advantage of the political process to do it – but I just didn’t want race to drop out at all, because it so permeates everything about the whole discussion.

And, the way the city talked about Fulton Mall was just so… They’d say things like, “There are really nice communities all around Fulton Mall. There has been this renaissance in all these communities, but you can’t use Fulton Mall as a way to connect them.” So in other words, right in the middle of this hyper-gentrification of the brownstone neighborhoods there is this spot that people don’t feel comfortable walking through to get from Carroll Gardens to Fort Greene and that’s a problem. The reason that it is a problem for folks is that it’s a culturally Black space. I’ve had White people say to me, “I feel I don’t belong there.” And then the question is: is that a problem? Maybe you don’t belong there. Does that mean it should change? Just to break open that conversation is part of the intention of the film.

NESRI: You have talked a lot about the scene in the film when you juxtaposed people at the farmers market in Park Slope and their views on the Fulton Mall with folks who grew up at Fulton Mall. Can you tell us more about that scene?

KELLY: I’ve actually gotten a lot of flack for that scene. Some White people feel it’s an unfair depiction – that it sets people up. Then I try to make the point these guys aren’t outliers. This is how people talk. Those residents aren’t raving racist people. They’re like all of us… They don’t know they’re being offensive. There is just this way that they feel – I think it’s a privilege thing: “My idea about that space is by definition the way everyone defines the space.” There is a universalizing of their perspective that’s really interesting and I feel like the City [of New York] really does that a lot. In a meeting with Joe Chan from the [Downtown Brooklyn] Partnership, he said, “Ten years ago, my friends wouldn’t live in Brooklyn.” This is symptomatic of the above sentiment, which I think is common. I always feel like responding, “Who cares? That’s totally irrelevant to public policy!” But, actually when I think about it, public policy is made, and justified, based on these seductive notions about what’s nice.

NESRI: Kelly, thank you so much for talking to us about your great film. We think it’s an important film about a really germane issue affecting our communities and are honored to be supporting it.

For more information about My Brooklyn, visit http://www.mybrooklynmovie.com and to find a screening of the film, jump here.