Chicago Anti-Evictions Campaign featured on Chicago PBS station WTTW

To watch a video of this report click here.

With crisis comes opportunity. That’s how one group of activists sees Chicago’s housing crisis, which has left the city with about 62,000 vacant properties, many rotting and unsafe. They call themselves the Anti-Eviction Campaign.

“We’re trying to create a people’s housing authority, not a public housing authority,” said J.R. Fleming, the brains behind the campaign.

Martha Biggs, who goes by the nickname “soul sister,” lives in one of the campaign’s takeover homes on the South Side.

Fleming co-founded AEC, which uses legal and not-so-legal tactics to rehab abandoned homes and move homeless people in, right after the housing bubble burst. Since 2009, it’s rehabbed approximately 30 homes, most on the South and West Sides.

“The city approach of spending $40,000 per unit to tear these buildings down is just absurd,” Fleming said.

Martha Biggs lives in one of the campaign’s so-called “takeover homes” in Grand Crossing on the South Side. It’s a foreclosure technically owned by Deutsche Bank.

Biggs was a long-time resident of Cabrini Green until it was demolished

“It’s cheaper to fix the building than to tear it down,” Biggs explains. “If you don’t want the gangbangers in the building, move a homeless woman in it with children. She’s going to keep them off her doorstep because she wants somewhere to stay.”

Biggs grew up with Fleming in the public housing project, Cabrini Green. For all its flaws, she says Cabrini was home.

“To me, it was life,” Biggs said. “Until we was misplaced.” After Cabrini’s demolition, Biggs spent the next 15 years homeless, sleeping mostly in her minivan or on friends’ couches while her four kids stayed with extended family. That is, until she started a conversation with the Anti-Eviction Campaign.

“They took me in and showed me the things that I could be doing to help the community,” Biggs said.

Now, she works for AEC rehabbing vacant houses. It’s a skill set she actually picked up in public housing.

Eric Ray, who lives with his sister on the same street as Martha Biggs, says the Anti-Eviction Campaign’s work has brought much-needed stability to his community

“In the projects, it comes a time that you got to wait forever for them to come fix something in your home, and you get tired of waiting,” Biggs said. “So basically you try to fix it yourself. Either you mess it up worse or you fix it.”

Eric Ray lives down the street from the home Biggs shares with a few others. He welcomed the idea of new neighbors in the long vacant house.

“I feel like drug users would have broken into the property and used it as a trap house to store drugs, to sell drugs, to have a warm place to be,” Ray said.

For the campaign, building community support like this is key. Before taking over a foreclosed home, workers canvas the block and ask neighbors point-blank if they’re comfortable with new residents moving in, even though these people won’t pay rent or a mortgage.

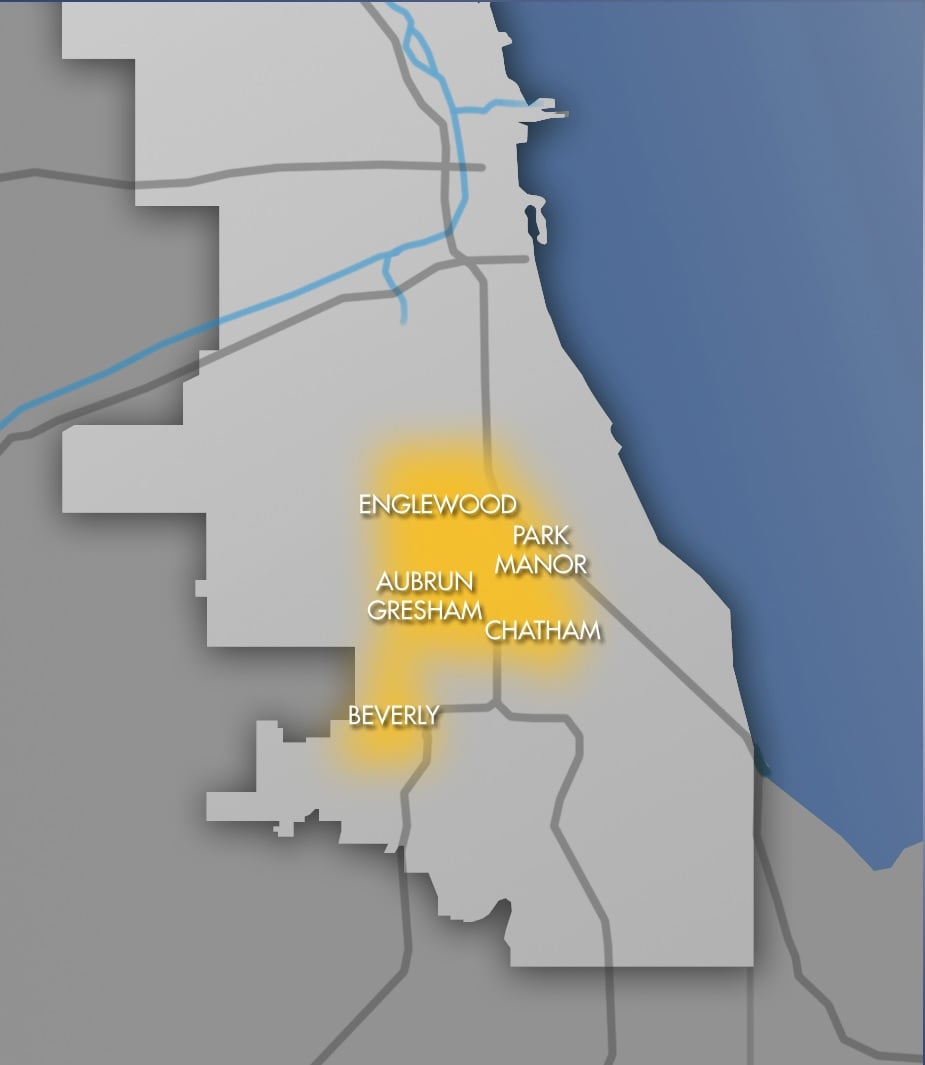

Chicago, at last count, has 62,000 vacant properties

For Ray, saying yes to the new neighbors was a risk worth taking.

“Every time I look out my big picture window, I see them cutting the grass or doing something to help the neighborhood,” he said. “They haven’t been no trouble.”

Down the street, AEC is taking over another vacant house. When it’s complete, the campaign hopes to move in a homeless mother and her kids. To ensure stability, AEC has new residents sign something called a “good neighbor contract” – a non-binding but formal agreement to be an asset, not a liability, to the neighborhood.

Anthony Hunter, who’s leading the rehab effort on the property, is one of a legion of unpaid volunteers who keep the Anti-Eviction Campaign running. The campaign gets some funds from foundations (e.g. the Crossroads Fund), but largely relies on volunteers like Hunter.

For Hunter, the project is a distraction that’s helping him heal. Hunter was shot on 75th Street a few weeks ago while trying to mediate a conflict.

“If there’s someone I can help, it makes me live longer,” he said. “I feel stronger.”

“They’re doing “Extreme Makeovers” on TV,” said AEC co-founder J.R. Fleming. “We’re doing extreme takeovers here in Chicago.” Here, a glimpse inside one of the Anti-Eviction Campaign’s rehabbed homes.

So, is this work legal? The answer: yes and no. The campaign has an interesting –sometimes friendly, sometimes antagonistic – relationship with banks, who technically own the houses they’re taking over.

“We basically negotiate with the banks and say, ‘Man, look, we’ll fix this property up, we’ll keep this grass cut, all we asking for is this lady don’t have to sleep in her car or don’t have to be homeless.’” Biggs said. “Nine times out of 10, they agree. They say, ‘Well, as long as she don’t mess this property up.’ But nine times out of 10, the property’s already messed up because you left it abandoned for four years.”

National research shows that, after forcing families into foreclosure, America’s banks have largely failed to market and maintain vacant homes, especially in communities of color. Without basic maintenance, the empty spaces become havens for crime, gun trafficking, and sometimes sexual violence, marring once vibrant neighborhoods. This is part of the reason the Anti-Eviction Campaign has expanded its work beyond rehabbing homes; the campaign also does legal assistance, connecting homeowners and tenants going through foreclosure with attorneys, and organizes protests against banks that, campaign staffers say, engage in predatory lending.

“It’s like being a deadbeat dad or a negligent partner,” Fleming said. “They’re not holding up their contract with the community, and we’re going to take it into our hands and do something with this property. Some cases we forewarn the banks and some cases we don’t.”

The way Biggs sees it, homeless people are keeping up the property in exchange for some temporary shelter.

“A homeless woman who ain’t got nothing to do can cut your grass, can keep the front of your house looking good,” Biggs said. “You, sitting in the bank, I don’t think you can do that.”

At the very least, the campaign tells residents to keep receipts for all the work they put into these homes. If the banks kick them out, at least they can petition to get reimbursed.

“Before we move in anybody, we tell them the risk associated with moving. They know it’s temporary. It’s not permanent,” Fleming said. “At the end of the day, it’s going to be the people who are going to take control of the situation when it gets real, real bad.”

Additional Resources

APeoplesHousingAuthority_CAEC_PBS_June2013

APeoplesHousingAuthority_CAEC_PBS_June2013