Human Rights, Social Justice, and U.S. Exceptionalism: A Conversation between Cathy Albisa and Meredith Tax

American politicians often talk as if human rights were only relevant in other countries, but grassroots organizations are increasingly using the human rights framework to win social and economic rights for the poorest and most marginalized people in the US. Cathy Albisa, director of NESRI, spoke to Open Democracy's Meredith Tax on this subject.

Meredith Tax: Looking at the history of human rights in the US, why do you think it has taken progressives so long to use the ideas of human rights for social and economic change?

Cathy Albisa: Progressives in the US have used the ideas for centuries, including in the abolitionist movement, but politics intervened after World War II when the formal human rights system was created. With regard to the United States, Carol Anderson spells out this history in her book Eyes Off the Prize: The United Nations and the African-American Struggle for Human Rights, 1944-1955.

People in the Civil Rights Movement recognized they needed a human rights strategy to achieve full equality because civil rights alone, without economic and social rights, would be inadequate. But at the same time, you had forces pushing in the opposite direction. On the international stage, the world was moving from a time of global unity against fascism to the East-West divisions of the Cold War. In this environment, human rights became highly politicized, with the USSR claiming economic and social rights and the US claiming political and civil ones. The cruel irony for people in both parts of the world was that the Soviet Union wasn’t adequately delivering social and economic rights and the US wasn’t actually delivering civil and political rights to a substantial portion of its population. But within the US, human rights became a political football and anyone who pushed for economic and social rights would be accused of aiding communism and being a traitor. And the Far Right had a very effective strategy of associating labor and human rights with what they described as the communist threat.

This dynamic was evident from the inception of the system. When the UN was first founded and the Charter was being negotiated in San Francisco, both the NAACP and the American Jewish Congress were there to link domestic issues to international human rights. The US government suddenly became concerned that they might be held accountable to this vision they were promoting for the rest of the world, and ensured a sovereignty clause in the UN Charter indicating that the system could not interfere in domestic concerns. Already, the United States saw human rights as a threat domestically.

Nonetheless, US leadership, in the person of Eleanor Roosevelt, was a key driver of the UHDR (Universal Declaration of Human Rights). Yet when the NAACP sought to use the international stage to make abuses against African-American visible, she threatened to resign from the US delegation to the UN. Eleanor wanted to keep human rights primarily an international vision to avoid political fallout at home.

MT: But she was being called a communist anyway.

CA: Right. She didn’t want to deal with any more attacks. And the backlash was so intense that conservatives almost succeeded in passing an amendment to the constitution, the Bricker Amendment, that would strip the presidency of power to enter and enforce treaties. It was stopped in the Senate in 1954 but it lost by only one vote. Eisenhower basically had to promise not to enter into and enforce any human rights treaties in order to make the threat go away.

MT: And their motivation was mostly racism?

CA: I think it was a package; there was both a racial component and an economic one in this toxic opposition to human rights. To give you an idea,Frank E. Holman, who was the head of the American Bar Association, went all over the country claiming Americans had to oppose human rights because they might lead to anti-lynching laws, mixed marriages, and desegregation. Clearly racism was a huge part of this, but human rights were also attacked as socialist. So at the moment of the founding of the UN, when the US might actually have embraced human rights within government institutions, the backlash became overwhelming. And because of this, the more mainstream people in the civil rights movement felt that they had to step back or they wouldn’t achieve anything at all.

The next visible effort to call for domestic economic and social rights came in the second wave of the civil rights movement with the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the Poor Peoples' Campaign, and Malcolm's call to place civil rights in the context of international anti-colonial struggles. But the civil rights movement was being seriously attacked at that time, people were being killed, and the community was so pressed it lost all faith or hope in the notion of American values and rights. Instead people understandably began to say they had to build their own power—that was the Black Power movement.

But the predecessors of the people now pressing for economic and social rights came out of that period. Marian Kramer from Detroit and George Wiley founded the National Welfare Rights Organization in 1966. George died in 1973 but Marion kept working even in periods where nobody else was talking about economics in terms of rights. The conversation was kept alive in the South as well, among African-Americans in particular.

MT: How did the US human rights movement develop after the 70s?

CA: First of all, you have to see the domestic human rights movement in the US as separate from the international human rights movement, or what we call the INGOs, International Non-Governmental Organizations. Though I wasn’t aware of much of a domestic human rights movement here until the early 90s, I have heard that even during the 1980’s there were efforts on the ground. But in 1989, the end of the Cold War prompted a heightened level of interest, because there was now a space where the ideas of human rights could be detached from international power politics and used for authentic social change.

In the early to mid 90s, new conversations began to develop about how to bring a human rights approach to the US. The two reasons that were cited—from the perspective of domestic advocates—was that we needed a more genuine definition of discrimination than the narrow legal version that prevails in the US. We needed a definition of discrimination that took on structural issues. And we needed economic and social rights. Those were the twin arguments I heard over and over again.

MT: Who was making these arguments?

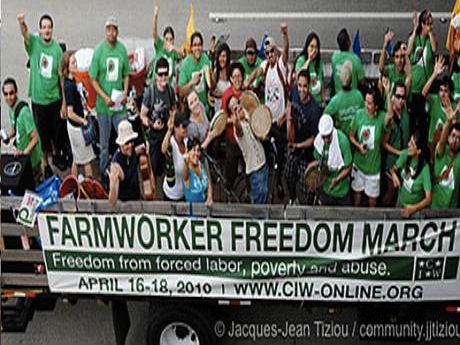

CA: There were two different types of people at the table in the early 90s. The first were from grassroots groups that had the seeds of a human rights analysis, small ones, welfare rights in particular, in Tennessee, Philadelphia, and West Virginia, and there were the public housing residents in Chicago. There was also the farm workers’ organization, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) which formed in 93. They started in a church with ten farm workers and copies of the UHDR which they read together, and were founded as a human rights organization from the beginning. They were from Mexico, Guatemala, and Haiti, and included founder Lucas Benitez and two graduates from Brown who were former legal services paralegals, Greg Asbed and Laura Germino. What they have built in Immokalee with a human rights vision is extraordinary.

The grassroots groups were interested because people were being crushed economically. When you look at the impact of Clinton's welfare reform, the bottom half of welfare recipients’ lives became far worse. So the first people I saw walk into the room were the most marginalized communities: welfare moms and farm workers. Things were so bad in farm work that in the 90s (and up until recently) there were several slavery cases in Florida prosecuted by the federal government, liberating more than 1000 workers and leading to up to 30 year prison terms.

In addition to the grassroots activists of the 90s, some lawyers were interested, like Deborah LaBelle in Michigan, who fought to stop rape in women’s prisons through litigation. And some international advocates were at the table, like Larry Cox, who later became the head of Amnesty USA but was at the Ford Foundation at the time, and Dorothy Thomas, founder of the Women’s Rights Division at Human Rights Watch. They thought the example of a US that wasn’t willing to be accountable to human rights standards even on paper was undermining the legitimacy of human rights worldwide.

So the movement spread from two poles: INGOs way up high and grassroots voices with very tiny organizations and very little money and power. And somehow this weird mix came together and started a conversation that’s now gone on for 20 years and has catalyzed new organizations and ways of working. Today you see a lot more people talking about economic and social rights partly because more people are feeling harmed—the students, the more traditional labor organizations, the people in Occupy. The AFL is increasingly using human rights messages and approaches, and claims to want to build analt labor movement, which looks at labor and community together, not segregating out issues but really trying see to how the web of society works.

MT: But the pivotal moment for US economic and social rights was the early 90s.

CA: Yes. And the movement was initially founded by communities that were being squeezed into the darkest shadows of the economy by the pressure of market fundamentalism—which Clinton promoted very strongly and which seeded the housing crisis as well as some of the economic problems we see today.

MT: We’ll have to remember that in the next election. And what about the US left? How does that deal with human rights?

CA: The US left obviously has some mixed attitudes towards human rights. Many of the older generation want nothing to do with human rights because it does have a very tainted history and they also think that kind of work can only be reformist. But some of us, and there is a generational difference here, believe that if we take the language literally at its word that it’s inherently transformative. The co-founder of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, Greg Asbed, and several of his co-workers were given the Roosevelt Award this year, the Freedom from Want award, and in his acceptance speech he mentioned the UDHR. He told me afterwards, “You know, I was looking at the audience and I could tell that a lot of people hadn’t even heard about it.” And that was in New York! He said, “It’s really a shame because if you take this little book seriously as a blueprint for society, it would be completely transformative.”

The UDHR is not only written in beautiful and poetic language, it has the right ideas and it sets a high bar if you take it at its word. What many people in the US human rights movement want to do is reclaim it and insist that it means what it says and it says what it means.

MT: Let’s talk about women and gender in terms of social and economic rights.

CA: I am not a person who privileges one set of rights over another by any stretch – but frankly, this is the set that shape most women’s lives because women are the ones who fill the gaps in a society that doesn’t protect economic and social rights. Usually it’s at the intersection of gender and race where you see the poorest people in society and it’s women who are the caretakers and have to watch their children go hungry and un-housed. Which is why it was women on welfare who were among the first to begin this movement.

The challenge is that there isn’t much of a women’s movement left in this country at all and, within the other social movements, there’s less of an explicitly feminist perspective than ever. I think some of that is changing but not through the growth of women’s organizations. I see it starting to change through more explicitly gendered discussion in non-women-led organizations.

Look at the Coalition of Immokalee Workers. They have made sexual harassment one of the four pillars of their Campaign for Fair Food, which has entered human rights agreements with eleven of the large produce purchasers including Taco Bell, McDonalds, Burger King, Subway, Whole Foods, and Trader Joe’s, to improve wages and working conditions in the tomato fields. Why sexual harassment? The depth of the problem became very clear when they started enforcing their Fair Foods Code of Conduct, which includes a worker-to-worker education process. And the women who were getting the education said, “You mean, this isn’t supposed to happen? You mean, I can do something about this?” And the complaints started coming in significant numbers and the women started getting more active and the female membership increased. And now they talk a lot about what women farm workers go through.

MT: Are you saying the CIW was started by men, so they weren’t aware of the issue, and as they tried to recruit women the issue came up?

CA: No. The co-founders included women. But it’s an 80 to 90 percent male work force and the CIW had to deal with a very degraded labor environment for everyone, and gender issues did not rise to the surface for a while. But here’s where the human rights approach comes in. They always saw themselves as a human rights organization, so when they entered into the agreements, they were committed to looking at the whole system and the full set of rights, and they automatically put in a prohibition on sexual harassment. What wasn’t clear was that this would end up becoming a signature issue. But when the enforcement began in 2009, this rose to the top, because for the first time the women in the fields were told, “Yeah, this can’t happen and we will do something about it if you file a complaint.” And many of them did. And they became far more vocal and far more visible.

The male leadership in the organization is as deeply invested in ending the sexual harassment and abuse as any women's organization I have seen. There is a deep solidarity in the organization. And you can’t do anti-sexual harassment work only vertically, you have to do it horizontally as well. So when they developed their public education, they couldn’t just go into the fields and say, “The boss is not allowed to sexually harass the women farm workers.” They had to talk about it more broadly. And they would give examples, “What if this happened to your sister, what if this happened to your mother,” you know, really trying to personalize it. At the end of the education session they would turn and say, “Well, these are your sisters and your mothers in the field when you are working together.”

It’s been amazing. And they will acknowledge that this as the hardest work they’re doing. It’s harder than ending the wage stealing. It’s harder than ending the violence. But that’s how gender gets integrated; people push for different kinds of structural changes and then the gender dimensions rise to the top.

MT: How does gender come up in other US domestic human rights work?

CA: In the domestic workers' movement, you see a lot of organizing led by women but you don’t see a lot of organizing that necessarily engages in an explicit feminist analysis.

In housing, we’ve done a lot of our work in public housing, which is 80% women. It’s one of those issues that people don’t talk about it in terms of women – there isn’t a real analysis, though it’s obvious that the predominance of women tenants in public housing has to do with the criminalization of black men and the feminization of poverty.

In our school-to-prison pipeline work there’s definitely a gender perspective because the schools target black males and that’s as important a gender perspective as anything else, though all students are affected. The Dignity in Schools Campaign has become more and more sophisticated at talking about the different nuances and manifestations of abusive discipline in targeting particular children. And now there’s a growing alliance and participation by the LGBTQ community in the campaign. That campaign started out with a classic school-to-prison lens and it has become more nuanced over time, especially around the sexual orientation work. And it is led by women at the parent level.

So it’s not that you don’t have movements led by women. But what we don’t have right now in this country is a lot of grassroots work that talks about the way women are specifically impacted. And I don’t know what the best solution is to that. I am really encouraged by what I see at the CIW and what I’d like to see is more integrated work, where gender is an explicit piece of it, rather than necessarily having women isolated.

And you do have groups like the Vermont Workers' Center. The Vermont Workers’ Center is probably—this is a big word I try to avoid in any kind of public discourse—but it’s probably the most intersectional of our partners. They’re an organization that’s mostly white because they’re in Vermont but they have a lot of anti-racism trainings and gender discussions. They’re very conscious on that level. I also believe their work on healthcare is feminist work, although because of the way women’s issues are defined in this country, healthcare financing somehow doesn’t make the list. Nurses are a disproportionately female profession and they have a close and deep alliance with the nurses’ union in this work.

The Vermont Workers’ Center explicitly supported reproductive rights in the new state single payer system, which commits to publicly and equitably financed health care. But I think we need to rethink what we talk about as women’s issues in this country. Because when you have a workers’ center coming together to campaign for public financing for health care in deep alliance with the nurses’ organization, I mean, these are women’s issues. It sometimes boggles the mind why we don’t see them as such.

In this country, women’s issues are defined to exclude anything that affects men as well as women. But that means we are defining women’s issues in relation to men! Because it’s much rarer for men to be targets of sexual harassment or rape, though it happens, those become women’s issues. Because men don’t get pregnant, abortion becomes a women’s issue. But that’s a very strange way to define what a women’s issue is. Even though most of the parents who work on education programs are women, education is not seen as a women’s issue unless there is some kind of discrimination.

MT: I used to do parent organizing and had arguments about whether this was feminist work. I would say, “I’m a feminist, I’m doing it, so it’s feminist work.” But some of my friends didn’t think a parent-initiated school was feminist work; it had to be something about gender roles.

CA: I’ve committed to seeing feminism as a perspective not a piece of work. I think, for example, when you try to raise your children in a democratic household, that’s feminist work, whether you are raising boys or girls. Sexism is predicated on the very notion of hierarchy and I think any time you try to challenge hierarchy and come up with other models of interacting and organizing yourselves socially, it should be seen as feminist work. Single-payer health insurance, is about creating shared risks—it’s a solidarity insurance system based on public financing, and that’s a feminist vision for the world.

About the authors

Meredith Tax has been a writer and political activist since the late 1960s, and is a Commissioning Editor at openDemocracy 50.50. She was a member of Bread and Roses, and founding chair of International PEN’s Women Writers’ Committee. She was founding President of Women’s WORLD, a global free speech network that fought gender-based censorship. Meredith is currently the US Director of the Centre for Secular Space.

Cathy Albisa is the Director and co-founder of the National Economic and Social Rights Initiative (NESRI) in the US. She is chair of the Board of the Center for Constitutional Rights. She was previously associate director of the Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School; co-director of the International Women's Human Rights Clinic at CUNY Law School; and staff attorney at the Center for Reproductive Rights and the ACLU.