Triple Jeopardy: Dismantling of the Public Sector and the War on Women

There has been much buzz in recent news surrounding the widening inequality gap, the long-term effectiveness of President Johnson’s Great Society programs in combating poverty, and President Obama’s call to increase the federal minimum wage. While these issues are extremely important, it has been surprising to see the lack of a gender lens in these dialogues, a perspective that is absolutely critical in evaluating potential policy changes.

Since the onset of the economic crisis in the mid-1970s, U.S. leaders have pursued a neoliberal agenda designed to downsize the government, and redistribute income upwards. Its familiar tactics include tax cuts, retrenchment, privatization, and deregulation, among others. To win public support for these unpopular ideas, neoliberal advocates have resorted to what Naomi Klein called the “shock doctrine”: the creation and manipulation of a crisis to impose policies that the public would not otherwise stand for. Discounting evidence and evoking the shock doctrine, government foes targeted programs for the poor but also popular entitlement programs—once regarded as the “third rail” of politics. Unlikely to pass Congress intact their proposals which fall heavily on women –will set the agenda for months to come.

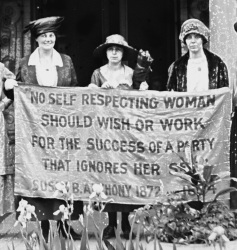

The current effort to dismantle the public sector is the latest round in the rancorous debate about the role of so-called “big government” that has shaped public policy since the mid-1970s. Initially targeted at program users, the attack subsequently took aim at public sector employees and union members. Since most scholars and activists focus on one group or another, they miss the strategy’s wider impact. Lacking the gender lens needed to bring women into view, they also miss that women comprise the majority in each group. Until the 2012 presidential campaign turned the women’s vote into a hot political issue, few officials paid much attention to women’s issues or did much to end the decades-long “war on women”

Given that women make up the majority of government service users, employees and union members, the cuts constitute a “war on women.” Many of the programs now on the chopping block address the basic needs of women and their families over the life span. Current House budgets proposed to to cut child care, Head Start, job training, Pell Grants, housing, and more by $1.2 trillion over the next 10 years.

Less spending by Washington translates into reduced federal aid to states and cities. To balance their budgets, states spent $75 billion less in 2012 than in 2011, and 31 states projected a $55 billion shortfall in state budgets for the 2012 fiscal year. In total, states governments have had to close more than $540 billion in shortfalls over the past four years due to cutbacks on the federal level. In addition, the right has taken aim on women’s reproductive health services, demanding ever more drastic cutbacks. In 2012, The Guttmacher Institute reported that legislators in 46 states introduced 944 provisions to limit women’s reproductive health and rights including massive cuts to Planned Parenthood.

Fewer services also mean more unpaid care work. Employed or not, women are the majority of the nation’s sixty-seven million informal caregivers; they pick up the slack when services disappear. From 1935 to 1970, the services provided by an expanding public sector helped women balance work and family life. Since the mid-1970s, neoliberal budget cuts shifted the costs and responsibility of care work back to women in the home. So does the growing practice of moving the elderly and the disabled from publicly-funded residential centers to home-based care, and discharging hospital patients still in need of medical monitoring and nursing services.

The anti-government strategy also decreased women’s access to the public sector jobs. After World War II, as social movements pressed for an expanded welfare state, these jobs became an important source of upward mobility for white women and people of color excluded from gainful private sector employment. In January 2012, women comprised 57 percent of all government workers. According to the latest available data, women comprise 43 percent of federal, 51.7 percent of state and 61.4 percent of local government employees. Women filled these jobs because society assigned care work to women, their families needed two earners to make ends meet, and social welfare programs benefited from cheap female labor. The public sector also became the single most important employer for blacks, who are 30% more likely than other workers to hold public sector jobs. More than 14% of all public sector workers are black. In most other sectors, they comprise only 10% of the workforce.

The Great Recession and the slow recovery have decimated public sector employment. During the early stages of the recession, men suffered more than 70% of total job loss because “male” jobs (construction, manufacturing, etc.) are particularly sensitive to cyclical downturns. The current “recovery,” by contrast, has been tougher on women, who comprised over half of the public workforce. From June 2009 to May 2012 as the public sector lost 2.6% of its jobs women suffered 61% of the job losses (348,000 out of 573,000). They gained only 22.5% of 2.5 million net jobs added to the overall economy. In 2012, the poverty rate among women climbed to an astounding 14.5%.

Total union membership plummeted from a peak of 35% of the civilian labor force in 1954 to just 11.3% in 2012 — the lowest percentage of union workers since the Great Depression. Private-sector unionization dropped to 6.6 %. Despite the loss of thousands of government jobs, public unions withstood the onslaught, maintaining an average membership rate of more than 35%. It helped that the majority of public sector work cannot be outsourced or automated.

Seeking to weaken the remaining unions, foes of labor and government turned against the public sector –labor’s last stronghold. Some governors demonized government workers as the new privileged elite to convince the public that collective bargaining rather than tax cuts is the enemy of balanced budgets. When governors strip teachers and nurses of their collective bargaining rights but spare police and firefighters, they hit women especially hard: 61% of unionized women but only 38% of unionized men work in the public sector. The loss of union protection sets women back economically. Unionized women of all races in both public and private jobs earn nearly one-third more per week than non-union women, although white women earn more than women of color. Trade union women face a smaller gender wage gap and are more likely to have employer-provided health insurance and pension plans than their non-union sisters.

Public sector unions historically pressed for high-quality services, dependable benefits, and fair procedures for themselves and for others. In the 1920s, the teacher’s union stood up for greater school funding and smaller class sizes. In the 1960s, unionized social workers fought for fair hearings and due process for welfare recipients. In the 1980s and 1990s, home care workers sought more sustained care for their clients. The loss of union power will cost public sector program users, workers, and union members a strong advocate. Unions remain one of the few institutions with the capacity to represent the middle and working classes and check corporate power inside and outside government.

The attack on the public sector puts women in triple jeopardy. As the majority of public sector program users, workers, and union members, they face fewer services, fewer jobs, and less union protection. In state after state, thousands of government workers and community supporters have raised up against these cuts, unwilling to take the assault on their well being, dignity, and rights lying down. As the National Economic & Social Rights Initiative reminds us, the current agenda amounts to “attacks on public responsibility, the notion of the public good, and the ability of government to secure economic and social rights for all.” These cuts pose as fundamental threats to the stability and health of both our country’s economy and our democracy. We must stand together to demand stronger social policies that support women and their families.

Mimi Abramovitz is Bertha Capen Reynolds Professor of Social Policy at the Silberman School of Social Work at Hunter College, and a Roosevelt House Faculty Associate; Faculty of the CUNY Graduate Center and the Murphy Institute for Worker Education and Labor Studies; Board member of the National Economic and Social Rights Initiaive.