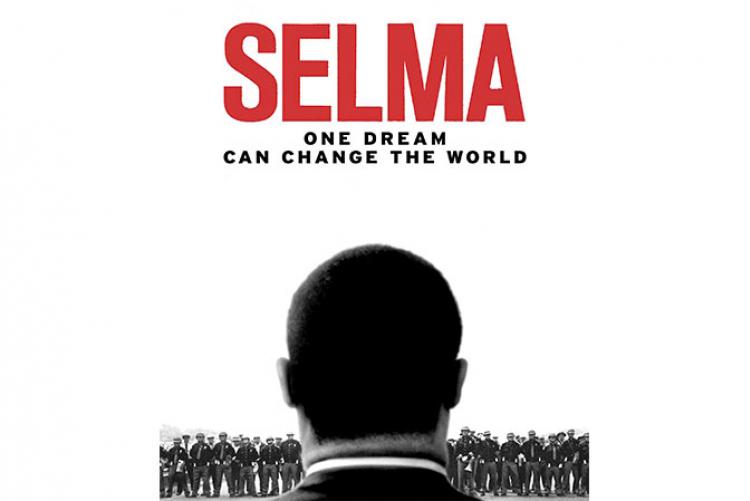

Personal Reflection on “Selma” from Gay McDougall, NESRI Board Member

The recently released film “Selma” attempts a deep-dive inquiry into one of the most pivotal series of events in modern American history. The movie is both ambitious and focused. In a little over two hours, it recalls the aspirations, courage and irrational brutality of an era that was so recent but yet nearly forgotten.

I remember.

Martin Luther King Jr. and his family lived around the corner from my home in the segregated Black neighborhood of Atlanta. Rev. Abernathy’s church was nearby and the SNCC (Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee) headquarters was not far away. The 1954 Supreme Court decision in the case of Brown vs. Board of Education and the Montgomery Bus boycott and other events that were rippling across our fields of dreams had given us all a sense that freedom was rising. But white resistance was fierce.

By 1965, when the events in the film took place, our forces for racial justice had achieved some sizable gains. There was the 1963 March on Washington, the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the well-publicized desegregation of a number of universities across the South. But can you believe that we were still being blocked from voting? Throughout the South the reality was that every trick imaginable was used to deny our 14th Amendment right to be full and equal citizens. And it was all backed up by violence. In 1964 three civil rights workers were killed in Mississippi while on a project to register African Americans to vote.

Ava DuVernay directed an account of the fight for voting rights that depicts the many personal and political currents that are always elements of transformative human dramas. While there was only space and time to make quick references to many of those currents, the film does not dumb-down or flatten out the complexities. ML King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s (SCLC) “ high-visibility” approach to making change was compared to SNCC’s preference for long-term community organizing. There was reference to the tensions between King and Malcolm X. Thank God Diane Nash was finally given her due, many histories of those times leave her and other women leaders out. The Reverends Bevel and Hosea Williams were represented and there was a nod to Andrew Young’s more cautious tendencies. Tim Roth was marvelous as George Wallace. Cuba Gooding Jr., playing the lawyer Fred Gray, represented the role played in the events by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and King’s insistence that the measures taken be legal.

And, yes, the depiction of President Lyndon Johnson’s reluctance to present the Voting Rights Bill to Congress in advance of his anti-poverty initiatives has been criticized by some as not reflecting accurately his high level of support for civil rights.

But what was more important to me, personally, was that when the camera focused closely on the face of Jimmie Lee Jackson’s 82 year old grandfather after his grandson—both of whom were active participants in the Selma protest–was murdered by a State Trooper, I saw a reflection of my father’s face and that of so many Black men of that era that I had known. These were men who had been denied every dream they had ever had. They knew pain, deep as wells. And they were still standing. DuVernay got that right. Her story was about these people. So, any slight to LBJ’s reputation can be corrected later by history.