US health news: Colorado to vote on universal publicly financed health care, 500,000 die from “diseases of despair,” pharmaceutical price gouging, and health care industry merger frenzy

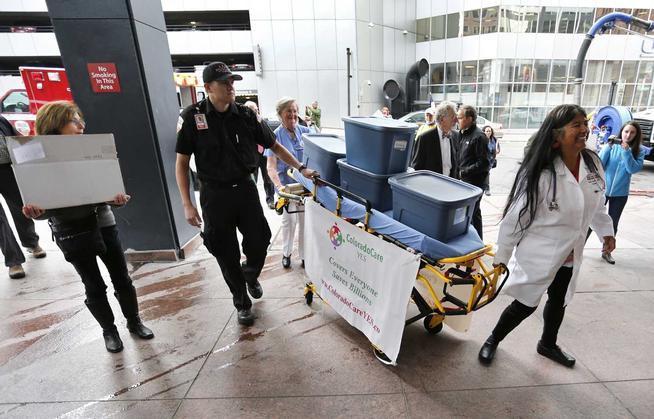

Colorado activists put universal, publicly financed healthcare on the ballot

Organizers in Colorado delivered over 150,000 signatures to the Secretary of State last month, putting an initiative on the November 2016 ballot that will let voters decide on whether to enact the country’s first universal, publicly financed healthcare system. The plan is not perfect: it could be financed more equitably, eliminate co-pays, include dental care and long-term care, and establish more robust mechanisms to ensure accountability to people’s right to healthcare. And because of federal law, states are not allowed to ban private insurers or create a truly unified publicly financed system. Nevertheless, the initiative would create a publicly financed healthcare system that would guarantee comprehensive healthcare to all residents of the state regardless of immigration status, marking a dramatic shift from a private insurance system toward a system that treats healthcare as a public good. It is far too soon to say, however, what the prospects are for the initiative to pass. Ballot initiatives can be a tool for democratic control and a way to circumvent recalcitrant legislatures, but they are also vulnerable to influence by powerful monied interests, which predictably employ anti-government, anti-taxation rhetoric to scare voters out of supporting important public policies. Just as everyone has been watching Vermont’s fight to win universal, publicly financed healthcare, people all over the country will now be watching Colorado as well.

Half a million White people have “died from despair,” and Black people are affected even worse

A new study has found that since the early 1990s, half a million poor and working class middle-aged White people in the United States have been killed by suicide, alcohol and drug poisoning, and alcohol-related liver disease. As The Atlantic reports, these are diseases of despair. This is a crisis of epidemic proportions rooted in social and economic inequities, but it’s not only White people who are affected. In fact, despite the focus of The Atlantic, the New York Times, and other media outlets on White lives, the study reveals that Black lives continue to be lost to these diseases at much greater rates. And while these deaths have been rising in the United States, in other countries with universal, publicly financed healthcare and strong safety nets, the study finds, such deaths have been falling continuously for the last twenty-five years.

5,500% increase in drug price draws widespread condemnation

A company recently drew widespread condemnation for buying the rights to a 62-year-old drug and increasing the price per tablet from $13.50 to $750 overnight. Several years ago, each pill was priced at just $1. Patients rely on the drug, Daraprim, to treat an infection that commonly affects people whose immune systems have been compromised by AIDS and some forms of cancer. The company sparked moral outrage, but it was operating both legally and rationally within a capitalist system in which healthcare is treated as a profitable commodity rather than as a human right. In the past year, several state legislatures have considered “pharmaceutical cost transparency bills” that would require drug companies to justify the prices they charge for medications. The bills would be a step in the right direction, but while transparency is an important part of a human-rights-based healthcare system, the bills would still leave much power over people’s access to healthcare in the hands of the pharmaceutical industry, and would do less to guarantee people’s access to medications than bulk purchasing, price controls, allowing imports, requiring drugs developed with public research funding be sold as generics, and other measures.

Mergers, collapse of coops and rate hikes highlight problems with the private insurance model

Three trends have developed this fall that illuminate structural problems with the private insurance model that remains under the Affordable Care Act. First, two planned mergers being considered by the Justice Department would consolidate control over the healthcare of 42% of the population in the hands of just three gargantuan insurance companies. The insurance industry mergers are mirrored by at least 78 hospital mergers so far this year and a similar “merger frenzy” among pharmacies and drug makers. In a related trend, a dozen nonprofit insurance “coops” have collapsed. The coops, which had offered insurance plans in many states, have been unable to compete against the insurance giants’ deep pockets and market power. And most recently, states have given insurance companies the green light to raise insurance premiums for publicly subsidized insurance plans by an average of 7.5% nationally and, for some plans, by more than 20%. At the same time, insurance companies are reporting that they will increase premiums on unsubsidized individual and small-group insurance plans by even more. The rate increases are all based on insurance companies’ profit motives, not on people’s ability to pay or their right to healthcare, and States have approved the increases with minimal transparency, participation and accountability.