Workers’ Comp Hub Newsletter: Fall 2016

This month we report on the history of domestic and farm workers’ exclusion from workers’ comp and other labor laws, looking at challenges and victories in organizing for change in both sectors. We also bring you news on gender discrimination and systemic denials in California’s workers’ comp system, and updates on trends in workers’ comp benefits, health and safety in the poultry and meatpacking industry, and the ongoing fight over employment status and labor rights in the sharing economy.

– Jim Ellenberger

Farmworkers and domestic workers fight exclusion from workers’ comp and other labor laws

This summer, the New Mexico Supreme Court ruled the State’s exclusion of farmworkers from workers’ comp unconstitutional. According to the New Mexico Center for Law and Poverty (NMCLP), which filed the suit, the ruling will extend workers’ comp coverage to between 15,000 and 20,000 farmworkers.

“It’s an important victory,” says Gail Evans, the Legal Director of NMCLP, “because it means that farmworkers in our state can finally get medical care and lost wages like all other workers in our state. And these are workers who need that more than most people.”

The Court’s decision stated that the exclusion was “nothing more than arbitrary discrimination,” and said that economic advantages for the agriculture industry could not come “at the sole expense of the farm and ranch laborer.”

Though farmworkers in New Mexico and everywhere else still face enormous challenges, this is a clear victory, and a good time to reflect on the historic and ongoing struggles of both agricultural and domestic workers.

Both farmworkers and domestic workers have always been excluded from workers’ compensation and other labor protections in many states. This exclusion stems from a long history of racial and gender-based discrimination. During the New Deal, for example, Southern representatives succeeded in exempting workers in both industries, who were mostly African American, from the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) to prevent Black workers and communities from gaining economic power.

Today, many of these unjust exclusions remain law, and, for a variety of reasons, farmworkers and domestic workers remain among the most vulnerable people in the workforce. They face serious health and safety hazards: farm work consistently ranks as one of the most dangerous occupations, and domestic workers have a higher risk for debilitating musculoskeletal disorders than workers in any other occupation. Workplaces in both sectors are under-regulated, and where health and safety rules do apply, they are rarely enforced. Workers in both sectors are also paid poverty wages, face rampant wage theft, and often have limited job security, leaving workers incredibly economically vulnerable. With most jobs in both sectors now filled by immigrants of color, many of whom are undocumented, threats and retaliation are rampant. Domestic workers (who are overwhelmingly women) and female farmworkers face the added challenges of sexism, sexual violence, and the devaluation of female labor. In extreme cases, workers in these industries fall victim to human trafficking and indentured servitude.

As Laura Germino, co-director of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW), remarks, “modern-day slavery cases don’t happen in a vacuum. They only occur in degraded labor environments, ones that are fundamentally, systematically exploitive.”

Challenging these unjust laws has not been easy. Farmworkers and domestic workers face significant barriers to unionization. In addition to the legacy of the New Deal exclusion, domestic workers tend to be employed in isolation, whereas many farmworkers are not directly employed by farm owners. Furthermore, organizing both workforces is made difficult by language barriers and the vulnerability than many immigrant workers feel because of their immigration status.

Yet despite the challenges and risks of organizing, workers’ organizations have been making big strides. In 2010, activists in New York won a major victory with the passage of a Domestic Workers Bill of Rights, which guarantees overtime pay, one day off per week, extended protection under the state’s human rights laws, and expanded workers’ comp rights (though these protections remain limited to full time workers). Domestic Workers United member Christine Lewis said that the 2010 bill made women in domestic labor “aware and conscious that there is a law that stands for them,” in turn empowering them to share stories and get involved in organizing. Since the New York bill was passed, six other states have passed similar legislation, with Illinois becoming the latest state to celebrate a domestic workers bill of rights this August. On a national level, domestic workers won another important victory in 2013 when the U.S. Department of Labor extended minimum wage and overtime pay to two million home health aides and personal assistants.

Farmworkers have also won significant advances within the past decade. The Coalition of Immokalee Workers has grown its Fair Food Program to cover thousands of tomato field workers from Florida to New Jersey, and in New York State, a lawsuit filed by the New York Civil Liberties Union, Worker Center of Central New York, and Worker Justice Center of New York is seeking to end the exclusion of farmworkers from the right to organize by arguing that the exclusion violates the State Constitution’s Bill of Rights. If successful, the lawsuit will protect all “concerted activity,” including collective bargaining, forming committees to discuss health and safety problems, and any action two or more farmworkers take together to improve their jobs.

While organizing is making a difference for farmworkers’ and domestic workers’ rights, there is still a long way to go. Farm laborers in sixteen states lack the right to workers’ compensation, while in twenty-one others, workers’ comp is limited by factors such as the type of work, number of hours, immigration status, and number of employees. Domestic workers face similar discrimination: employers in twenty-five states are not required to provide workers’ comp for domestic employees and in most other states workers’ comp protection is limited based on time and earnings.

Inclusion in workers’ comp is not the end goal: workers’ comp is not getting workers timely, adequate care and lost wages in any sector, nor will inclusion in workers’ comp address the many other challenges that farmworkers and domestic workers face. But farmworkers’ victory in New Mexico is nevertheless a step toward ending the unjust exclusion of workers from critical protections and a cause for celebration.

Delays and denials in California’s workers’ comp system

In California, a series of investigative reports have drawn attention to widespread delays and denials in the workers’ comp system that cause lasting harm to injured workers. California bases its workers’ comp decisions on “utilization reviews,” which are partial computerized medical reviews done by insurance company doctors who never actually see the patients. The reviews pad the profit margins of insurance companies by denying care and income supports to workers. In one survey, 67% of treating doctors reported difficulty getting authorization from workers’ comp insurance companies to go ahead with needed treatments. There is also a lack of transparency in the system; the only available report on how many workers’ comp applications are approved or denied comes from California Workers’ Compensation Institute (CWCI), a private industry organization with data voluntarily submitted by its members. Two bills are on the table in California State Legislature that would help injured workers receive timely, adequate care. SB1160 would increase the timeliness of utilization reviews, while SB563 would prevent insurance companies from offering financial incentives to evaluating doctors based on the number of denials and delays they issue.

Illinois Governor continues assault on workers’ comp

In Illinois, Governor Bruce Rauner wants to cut or eliminate benefits for many injured workers. Rauner wants to exclude all injuries that are not caused “more than 50%” by an incident at the worker’s current employer. This means that if an injured worker’s condition has complex causes that involve or may involve multiple contributing factors, her workers’ comp claim may be denied. Dave Menchetti, a workers’ comp attorney in Chicago, says the measure “would severely prejudice older workers and workers in heavy industries because those are the kind of workers who have pre-existing conditions.” He also points out that doctors are not trained to quantify the causes of an injury, making such a formula arbitrary and open to unjust influence from employers and insurance companies. A report by In These Times highlights the competition over employers with neighboring Indiana, making the two states a classic example of the workers’ comp “race to the bottom.” To back up his push to cut comp benefits, Gov. Rauner has been touting the threat that employers will chase cheaper costs and head to Indiana, evoking the “spectre of the vanishing employer” that was debunked by the 1972 National Commission Report of the National Commission on State Workmen’s Compensation Laws but is still often trotted out by politicians and business lobbies to this day.

Uber drivers finally recognized as employees in California

Rejecting a $100 million settlement proposed by Uber’s lawyers, U.S. District Court Judge Edward Chen said that the company’s drivers should be classified as employees, entitling them to the right to organize, workers’ comp, and other important workplace protections tied to employee status. Chen noted that although Uber does not control hours, they do control hiring and firing as well as other aspects of the job. He also pointed out that the settlement grossly undercut the claims from the drivers filing the class-action lawsuit, which totaled $854.4 million.

California women call out gender discrimination in workers’ comp

A group of female workers and the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) California State Council have filed a class action lawsuit calling out gender-based discrimination in the California workers’ comp system. Their claim cites systemic biases that reduce women’s workers’ comp benefits by attributing work-related injuries and illness, particularly carpal tunnel and breast cancer, to pregnancy, breastfeeding, menopause, or other gender-related “risk factors”. Psychiatric conditions such as depression are also reduced, by as much as 80%, due to vague assumptions about reproductive factors. The state’s workers’ comp system “deprives women workers of fair compensation on the basis of stereotypes about gender and women’s reproductive biology,” says the complaint, adding that “by permitting and condoning the distribution of workers’ compensation benefits on the basis of sex, the State of California sends a clear message that women’s work is worth less.” For more about gender discrimination in the comp system, see our previous story.

New reporting rule from OSHA turns up revealing data from meatpacking industry

In July, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) imposed a fine of $78,000 on poultry supplier Pilgrim’s Pride for denying access to medical care to injured workers at their Florida, often leading to prolonged and exacerbated injuries. The poultry industry is known for the particularly horrible health threats their employees face. Inadequate safety equipment and training regularly lead to chemical burns, zoonotic diseases, and crushed limbs, while Oxfam reports that poultry industry workers have ten times the rate of repetitive strain and seven times the rate of carpal tunnel than the rest of the workforce. Workers are fearful of reporting injuries and safety hazards, even to inspectors, because of threats of retaliation from their supervisors. While it is important that OSHA is holding the poultry industry accountable, the fine for this violation remains too low, giving little more than a slap on the wrist to Pilgrim’s Pride. “Until the financial consequences of mistreating workers becomes greater, we’re going to keep seeing these kinds of conditions being endemic to the industry,” says Naomi Tsu, Deputy Legal Director for the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC). Debbie Berkowitz, a senior fellow at the National Employment Law Project, adds that “This is about dignity and justice for the workers. It’ll take quite systemic change for these things to be in line for full rights and dignity for workers.”

Reports show workers’ comp benefits diminishing

The Department of Labor has released an important report detailing the history of workers’ comp and assessing how the current situation affects injured and ill workers. Emphasizing that only a small proportion of the costs of occupational injury and illness are covered by employers, the report highlights several state legislative trends that have led to decreased benefits for workers. These include more exclusionary standards, decreased cash benefits, programs that discourage reporting of injuries, and restrictive rules for procedure and evidence. The report calls for a “significant change in approach in order to address the inadequacies of the system” and recommends further exploration of instituting federal minimum standards and re-establishing a national commission.

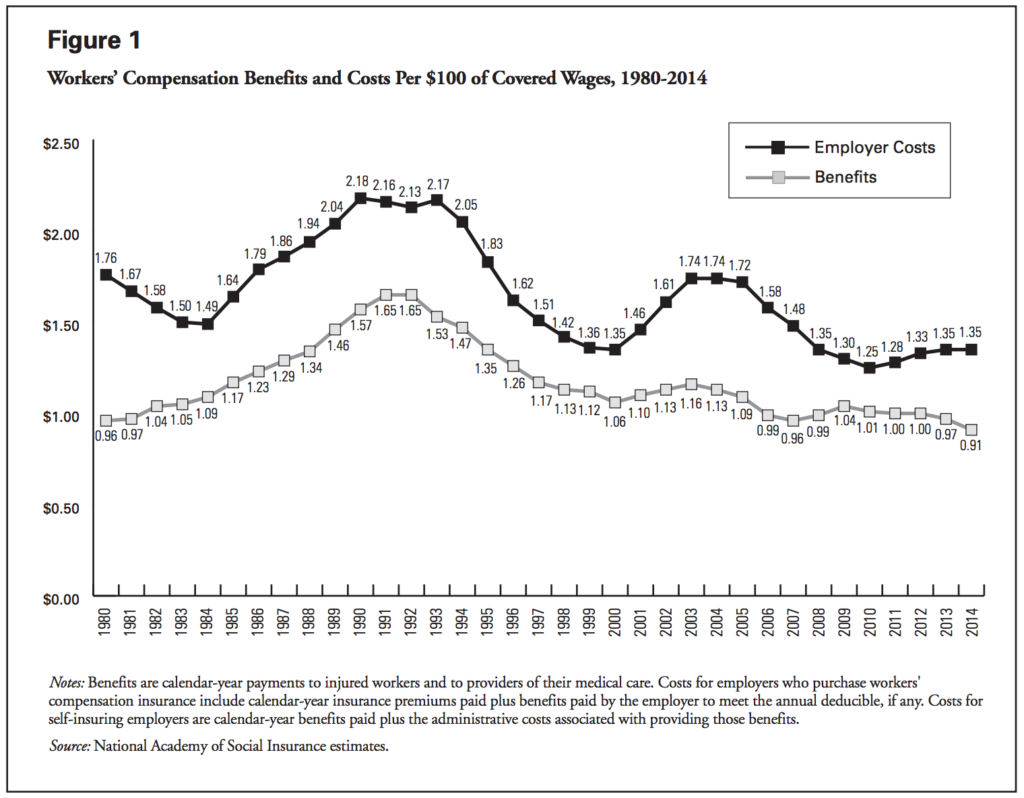

The National Association of Social Insurance has also released its annual workers’ comp report on trends in costs and benefits. Among its findings are that workers’ compensation benefits decreased for the second year in a row in 2014, in line with a general trend since the early nineties (see figure above).

Events

National conference on worker safety and health 2016

The National Council for Occupational Safety and Health (COSH) will hold its annual conference on December 6-8. Along with speakers, panels, and networking events, the conference features 45 interactive workshops on organizing and advocacy strategies, legal rights, chemical hazards, and other training topics for safety activists.

Reports

Department of Labor finds workers’ comp fails to provide adequate support to injured and ill workers

The Department of Labor issued a report reviewing the history and current state of workers’ comp, and calling for renewed federal oversight of state comp laws.

Benefits, coverage, and cost trends

The National Academy of Social Insurance released their annual report of workers’ compensation trends, showing benefits paid to injured workers decreased in 2014.

Denials and delays in California workers’ comp

In this series of three investigative reports, NBC Bay Area reveals widespread, routine denials and delays in California’s workers’ comp system and looks at how this hurts injured workers.

‘Race to the bottom’ in Illinois This report from In These Times looks at proposed changes in Illinois workers’ comp law that would exclude many injured workers from coverage.

Pound Civil Justice Institute symposium papers

The following papers were presented for a symposium on “The Demise of the Grand Bargain: Compensation for Injured Workers in the 21st Century”, which examined how contemporary legal, political, and labor changes have affected workers’ comp.

Work Injury and Compensation in Context,1900 to 2016

Emily Spieler, Northeastern University School of Law

Workers’ Compensation at a Crossroads: Back to the Future or Back to the Drawing Board?

Alison Morantz, Stanford Law School

Can State Constitutions Block the Workers’ Compensation Race to the Bottom?

Robert F. Williams, Rutgers Law School

Outside the Grand Bargain: The Persistence of Tort

Robert L. Rabin, Stanford Law School

Towards a Less-Grand Bargain for Injured Workers

Adam Scales, Rutgers Law School