Democratizing Workers’ Compensation: Our Final Workers’ Comp Hub Newsletter

Dear readers,

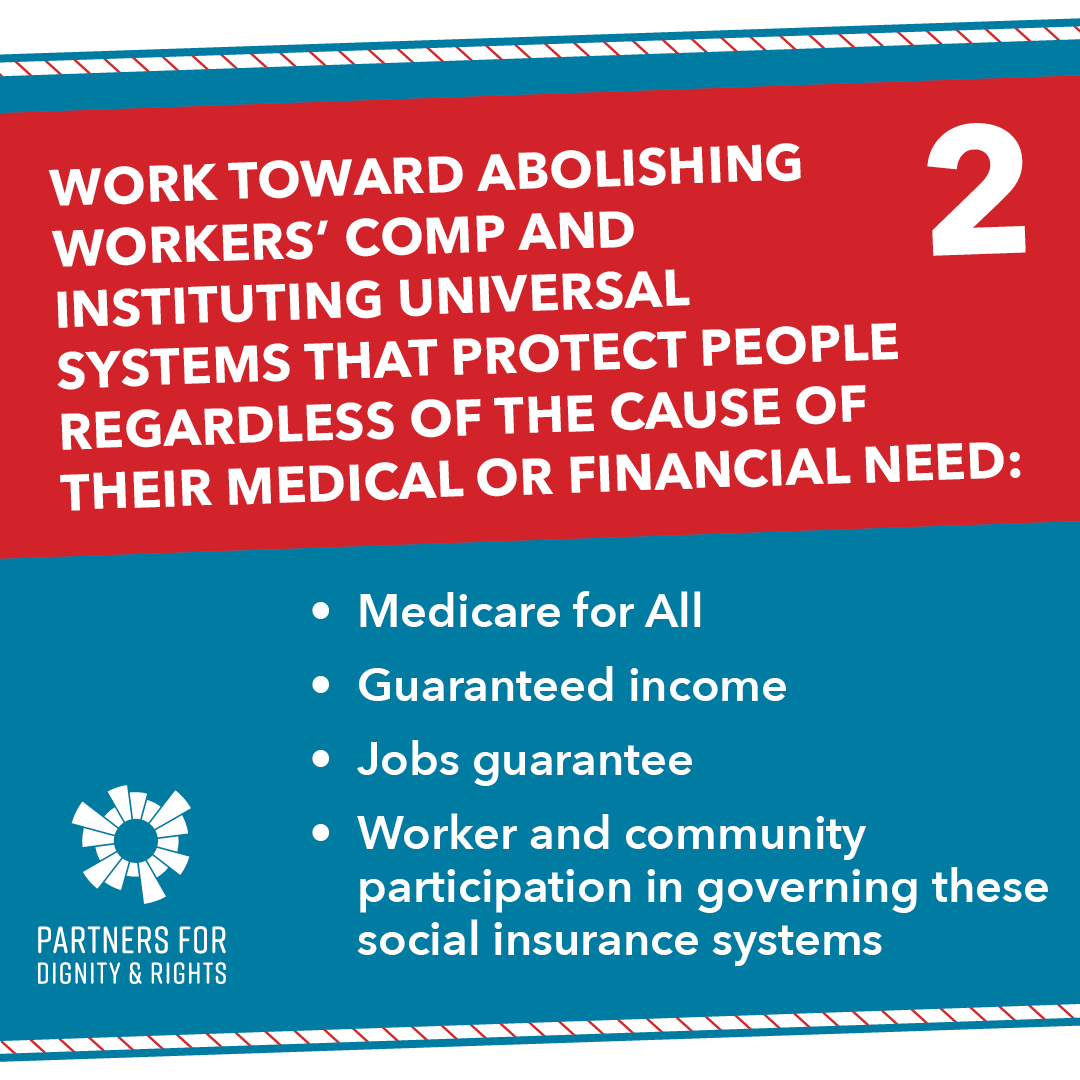

Since Partners for Dignity & Rights and National COSH teamed up ten years ago to launch the Workers’ Comp Hub website and newsletter, a lot has happened in the world. Our movements have won big advances in our fights for justice, dignity and human rights, yet as we all now, the threats facing workers remain severe. We remain as committed as ever to worker-led organizing and advocacy that centers the needs and leadership of workers who have been hurt, sickened or disabled in this work. Yet over the years, it has become clear to us that the path toward justice for injured and ill workers does not lead through workers’ compensation alone. Rather, what workers need is a broad, multi-faceted labor movement to build worker power and to win worker-centered policies and institutions that meet all of workers’ needs for healthy, safe, dignified work, compensation, health care and rehabilitation. This movement must be part of larger struggles for racial, economic, gender, disability and other forms of justice in and out of the workplace, but without losing sight of the unique needs of injured and ill workers.

We have therefore decided to close the Workers’ Comp Hub, migrating the news and resources we developed onto Partners for Dignity & Rights’ website, and to discontinue this newsletter. As a final offering, we are pleased to present a new offering from Partners for Dignity & Rights: a report on opportunities to democratize governance of workers’ compensation (and workplaces, social insurance and health care at large) in order to give workers more individual and collective power to claim their fundamental rights.

This may be our last Workers’ Comp Hub newsletter, but we invite you to subscribe to our both of our organizations’ newsletters and to follow us on Twitter (COSH/P4DR) and Facebook (COSH/P4DR), and to join us at the next National Conference on Worker Safety and Health. We wish to thank the Public Welfare Foundation for helping conceptualize and support the Workers’ Comp Hub over the years, and wish to thank all of you, our readers, for your commitment to the dignity and rights of workers.

In solidarity,

Ben Palmquist, Partners for Rights & Dignity

Marcy Goldstein-Gelb & Jessica E. Martinez, National COSH

The Future of Workers’ Compensation: Shifting Power to Ensure Workers’ Health, Safety and Economic Stability

For decades, companies have used every tool they can find to eat away at workers comp, and in so doing, to erode workers’ safety and health. The problem has inevitably reached a crisis point during the pandemic, as workers sick with COVID were often denied workers’ comp on the grounds that they could not prove that they contracted it at work. However, the underlying issue has been brewing for years, with corporations and their owners making decisions with impunity that directly affect the health and safety of their workers. This dynamic will only be resolved when this power imbalance is rectified, and workers are able to have a meaningful say on issues that directly affect them.

Essential Workers at Risk

COVID-19 has made clear that big changes are needed in how the U.S. structures work and health care. Among those hit hardest by the pandemic are low-wage workers in the service industry, medicine, nursing homes, agriculture, warehouses and meatpacking plants. Their jobs require physical presence, often in close contact with co-workers and/or the public. Workers at meat processing plants and other factories must work in tightly packed lines and often travel together in crowded buses to work sites. Similarly, farmworkers often live together in cramped quarters and travel together in packed buses. Both these plants and farms continue to be COVID-19 hotspots. In the service industry, workers report that on top of constant close interactions that increase their risk of contracting coronavirus, tips have gone down and incidents of sexual and other forms of harassment have spiked.

Despite the high risk they face, these workers have struggled throughout the pandemic to get their employers to take the necessary precautions to protect their health and prevent the spread of coronavirus at their workplaces. Across the board, workers are more afraid than ever to speak up on the job for fear of losing work in the current economy, while, at the same time, many still work in fear of contracting the virus. Workers deemed “essential” were forced, living paycheck to paycheck, to continue to go in to work, while others, particularly in the service sector, lost work and have struggled to make ends meet (especially undocumented workers). Now, with most of the economy reopened, those who have been out of work are in dire need of income and are consequently more vulnerable than ever to accepting jobs with abusive conditions.

In fact, rather than protect workers and, thus, the public, many states have spent their time and resources over the past year shielding employers from accountability for inadequate pandemic precautions. At least ten states have passed legislation that gives companies immunity for failing to protect workers, while a number of others have similar bills on the docket right now. Re-opening decisions have been dominated by Chambers of Commerce and business interests, while frontline workers who would be the most knowledgeable and the most impacted by these choices, have been largely left out of the decision-making process. This has inevitably led to the dynamic in which those who are setting the standards can focus on profits and efficiency, while ignoring the need to protect workers’ health and, with it, public health.

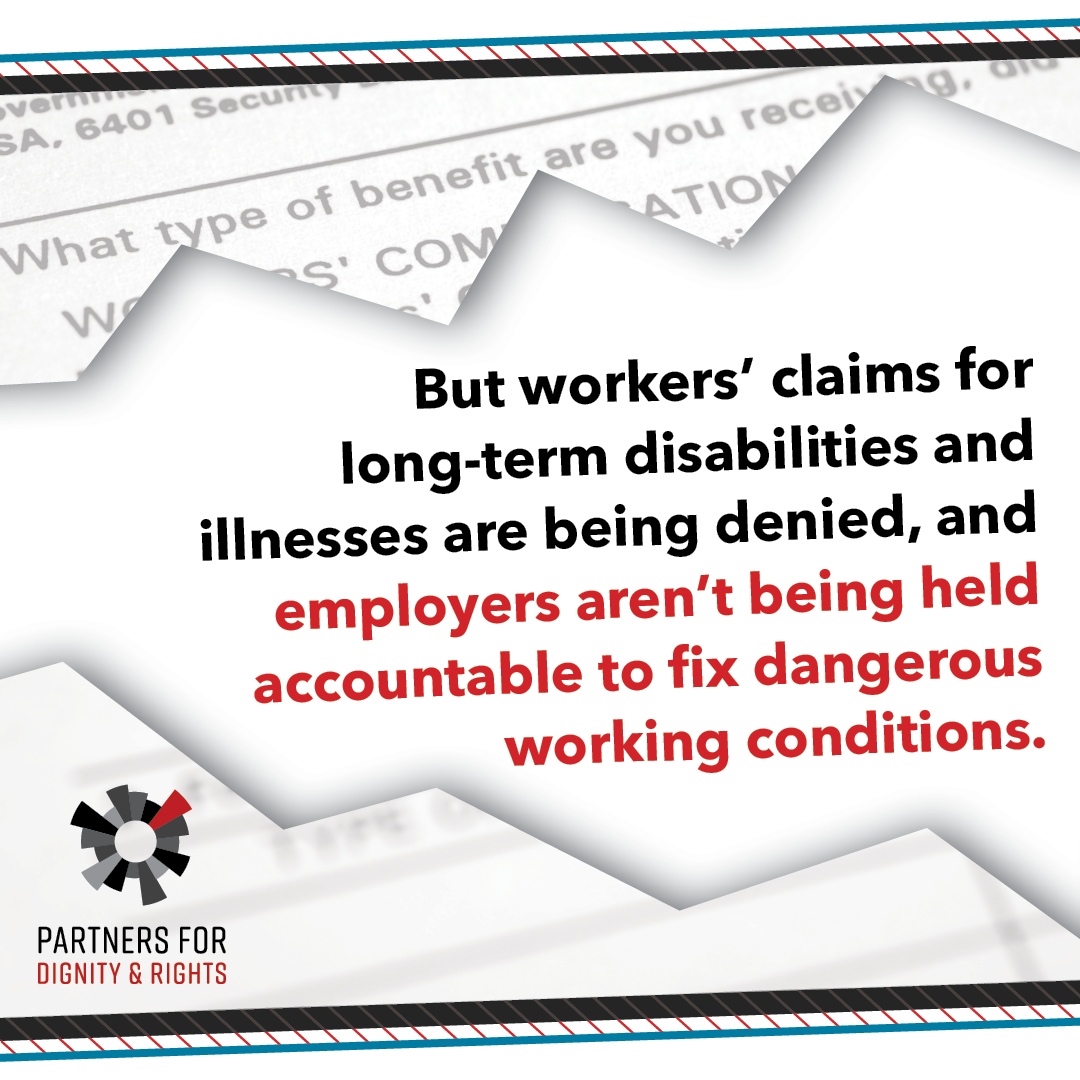

Meanwhile, workers and labor advocates report that it has been nearly impossible for essential workers who contract COVID-19 to get workers’ comp claims approved. Even as insurance and business groups publicly promote the image that they are taking a “liberal approach” in evaluating workers’ comp claims for Covid-19 patients, workers (including nurses) are seeing their claims denied with the rationale that they could have contracted the virus outside of work.

With millions of people now getting COVID vaccines every day, the end of this acute early phase of the pandemic is coming into sight. Yet the virus has surfaced long-standing vulnerabilities and inequities hurting U.S. workers—problems that require big changes to shift power to workers.

Organizing for Workers’ Safety and Workers’ Compensation

Amidst worker deaths, inadequate protective equipment, and lack of communication about workplace infections, workers across the healthcare, service, e-commerce, and other industries have banded together to conduct walkouts demanding personal protective equipment, deep cleanings, safer conditions, and time to quarantine and recover.

In California, Kentucky, Illinois, and other states, workers have won important legislative changes that make it easier for essential workers to claim workers’ comp benefits. These laws create a presumption that essential workers who fall ill with COVID-19 are eligible for workers’ comp, shifting the burden of proof onto employers to show that the disease was not contracted at work. This is a major victory for workers who have assumed overwhelming health risks to continue serving essential social needs during the pandemic. Yet in many states, proposed bills are either still pending or have been voted down. Among those states that have passed laws granting presumptive eligibility, the categories of workers covered by the law varies significantly.

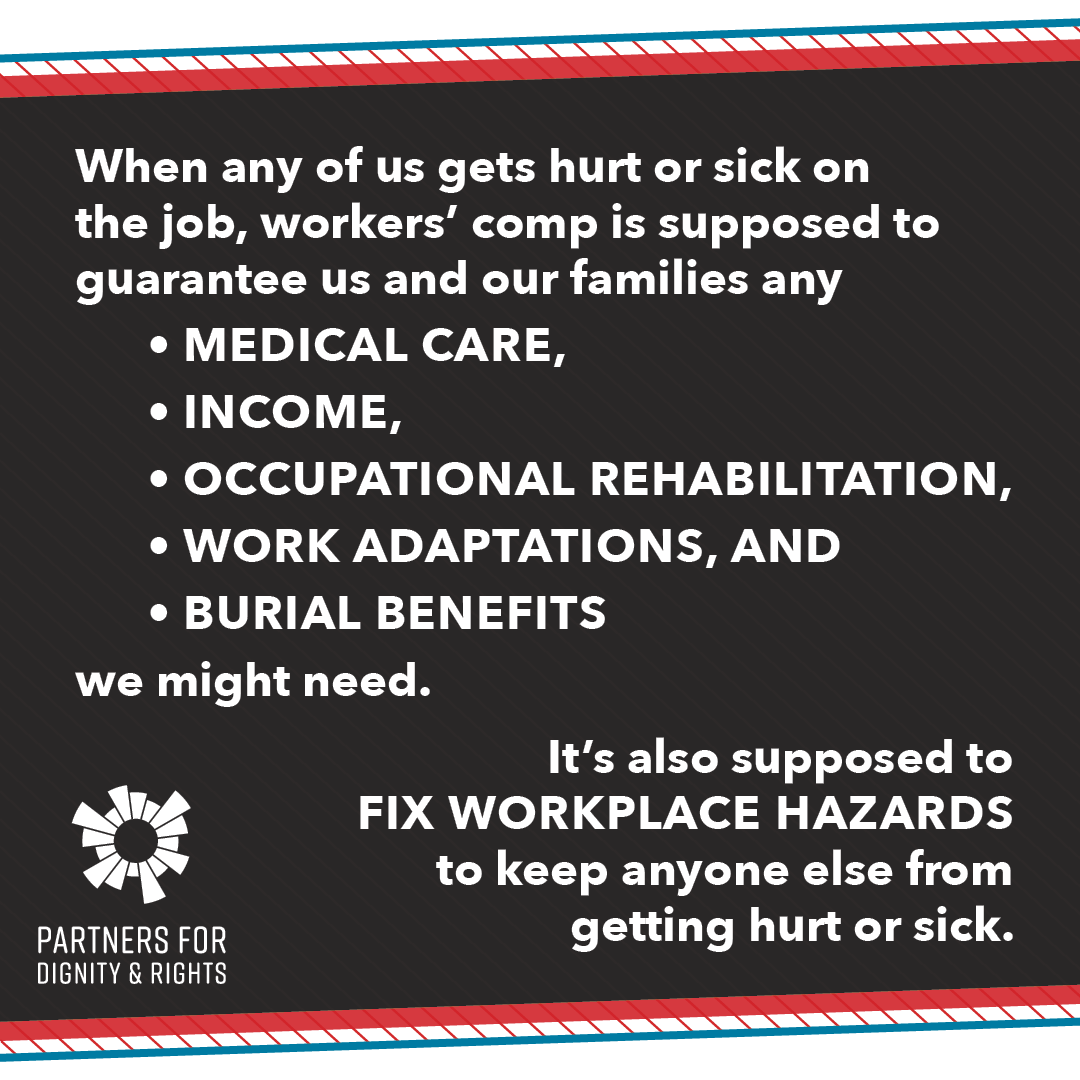

These laws are crucial and urgent. Workers’ comp, where accessible, is the most comprehensive and long-term existing protection for workers who contract COVID-19. However, even where such presumptions can be won for essential workers, the staunch resistance and scaremongering already seen from insurance and business groups foreshadows tough future battles over workers’ comp protections. Long-term trends and patterns in workers’ comp legislation show that increases in worker protections are reliably met with fierce and often successful pushback from industry lobbyists, who mobilize the rhetoric of job-creation to fight for lower insurance premiums — at the expense of crucial protections for injured and ill workers. Such tactics have contributed to the gutting of meaningful and reliable worker protections in the comp system over the past two decades, contributing to the frighteningly precarious position in which many essential workers now find themselves.

Shifting Power to Workers

Such perennial attacks on protections for injured and ill workers, along with chronic under-enforcement of workplace health and safety, indicate the need for a major shift in power. Leading worker centers are stressing that workers and workers’ organizations need a permanent, formalized role in standard-setting, monitoring, and enforcement. Workers know their workplace environments best and are aware of the risks they face in their daily work tasks. This experiential knowledge makes them frontline defenders of our community health. Their voices and experiences must be front and center in decisions over safety standards as well as protections and care for injured and ill workers.

In a new report, Partners for Dignity & Rights highlights several mechanisms that hold potential to bring empowered participatory governance into workplaces and workers’ comp, each of which is described in more detail in a new fact sheet from Partners for Dignity & Rights.

Introducing Accountability into Existing Workers’ Compensation Systems

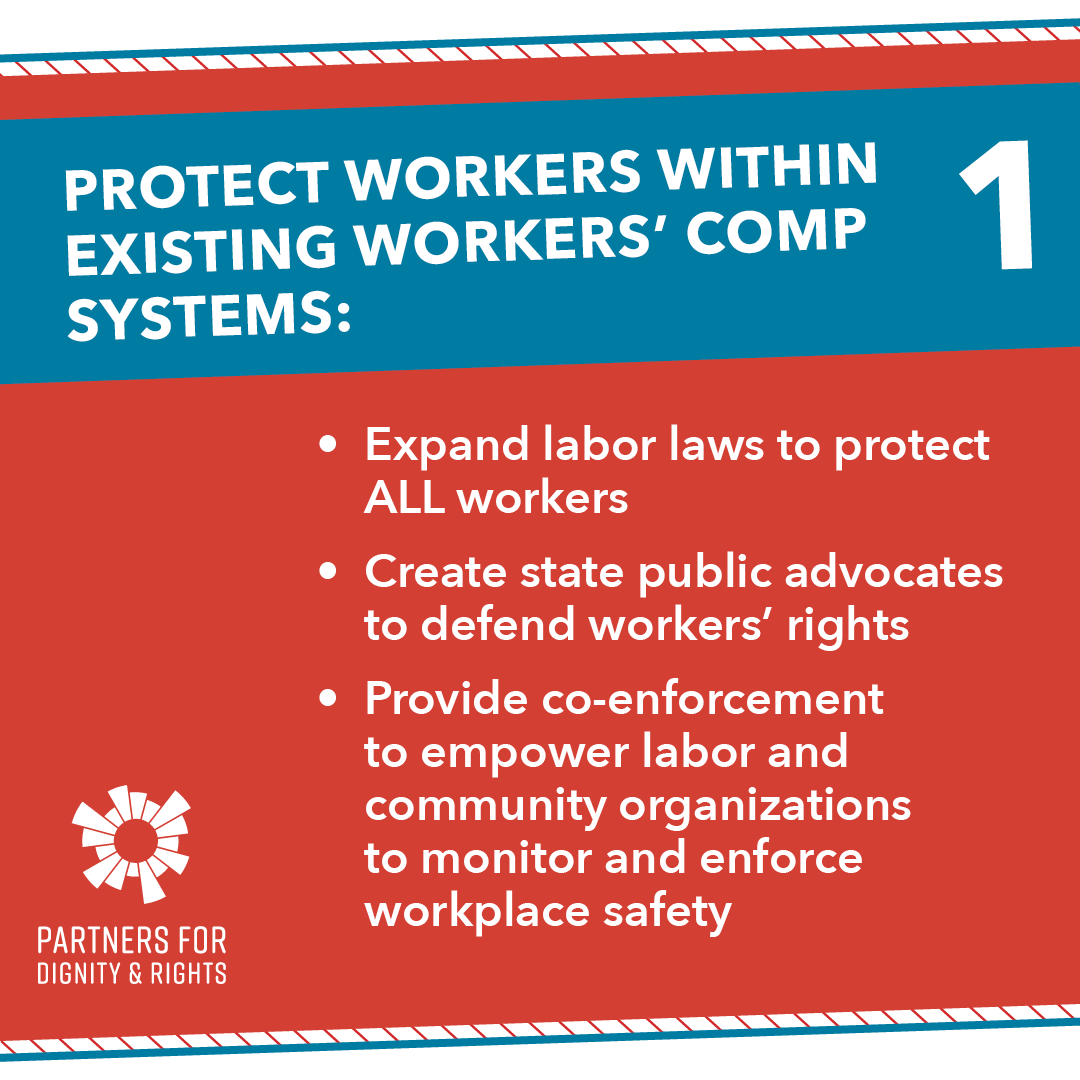

State departments of labor and state legislatures could introduce several measures to improve accountability in existing workers’ compensation statements. Two immediately applicable democratic tools that can help hold insurance companies, employers, and administrative agencies accountable are public advocates and participatory monitoring institutions. Both address individual cases of rights violations and insurance delays while also working toward systemic improvements in health and safety.

They could create public advocates like Nevada’s Office of Consumer Health Assistance (OCHA) to provide direct support to people who face wrongful claim denials, investigate systematic problems involving private insurance companies and public agencies, and act as peoples’ representatives in legislative and regulatory processes. OCHA, for example, has six full-time ombudsmen to assist residents with insurance problems, including a designated ombudsman just for workers’ comp. The office collaborates with labor and legal aid organizations to help thousands of residents appeal denied claims each year. Public advocates for injured and ill workers in other states would provide an invaluable resource to individual workers and would also serve workers as a class by advocating for injured workers’ rights in legislative and administrative hearings and amplifying injured workers’ voices in pushing for worker-centered reforms.

Participatory monitoring (also called citizen audits) empowers workers to hold employers accountable for workplace violations. Participatory monitoring is an institutionalized worker-led process in which workers are empowered and resourced to proactively audit working conditions and respond to worker complaints with investigative and enforcement measures. This model has a proven track record in protecting the health and dignity of vulnerable workers, and is increasingly being introduced into new arenas such as a new Los Angeles County program enabling workers’ organizations to help workers form workplace health councils in frontline industries to ensure that COVID safety measures are being implemented. Participatory monitoring could be extended to address problems specific to workers’ comp, such as retaliation for reporting injury or illness and filing claims, employer handling of return-to-work, and access to immediate care for acute injuries.

Participatory needs assessments are a model that can be introduced into the governance of state workers’ comp programs to help state officials better understand how workers’ comp is and isn’t serving workers so they better respond to workers’ needs. Officials work with labor and community organizations to research and document injured workers’ medical, social, economic and other needs in order to inform workers’ comp policy.

Participatory needs assessments can, in turn, be used in conjunction with participatory budgeting, which involves members of the public and, ideally, community and labor organizations, in making decisions about how public resources are distributed. Taken together, state departments of labor that manage workers’ compensation systems could use these mechanisms to make workers’ comp more responsive to worker needs and experiences and to make sure that states are directing resources toward meeting the needs of workers who face the biggest hurdles in getting medical care, income supports and work adaptations, including low-wage workers and workers with chronic musculoskeletal injuries or chronic illnesses. State workers’ comp boards could begin by commissioning participatory needs assessments and opening a portion of their budgets to participatory budgeting, and could place requirements on publicly financed institutions and companies contracting with the state to similarly introduce these participatory governance mechanisms.

Growing Workers’ Power Outside of Workers’ Compensation Systems

In the longer run, we can continue to build labor power for a more equitable and democratic economy by expanding the scope and organization of collective workplace governance. Codetermination and tripartism hold promise as two broad models of shared governance at both the corporate and regulatory levels, while democratic ownership combines co-governance with worker ownership. All three approaches work alongside and with existing worker organizations, strengthening collective bargaining power and expanding worker representation beyond current employer-by-employer unionization.

Codetermination is a European model of labor organization comprising three layers of worker participation, combining shop-floor works councils and worker representation on company boards with national-level union bargaining. A 2019 study on German codetermination shows that more robust occupational health and safety measures are correlated with workplaces that have active works councils.

Tripartism is an institutional framework that places worker or community organizations in a permanent third-party role alongside government regulatory agencies and industry organizations. A robust form of tripartite governance would give a wide purview of shared powers and responsibilities to worker representatives. For the regulation of health and safety standards and workers’ comp employer responsibilities, this would mean designating a permanent position for unions, workers’ centers, or other independent NGO’s who would have full access to the information held by state regulatory agencies, equal powers of investigation and enforcement, and a seat at the table in negotiating policy changes.

Finally, democratic ownership offers an alternative model for sharing company profits and management, transforming company power relations and profit incentives at the root. Worker-owned companies place worker safety and quality of life, rather than cost-cutting, at the center of their priorities. Existing worker cooperatives, one form of democratic ownership, have secured higher and more equitable pay for their owner-employees, while also proving more productive than traditional businesses.

Amidst the unprecedented, cross-sector workplace health and safety crisis created by COVID-19, there is growing recognition that structural changes are needed to protect workers’ lives. The mechanisms of participatory governance presented here can be implemented at a number of different levels, and in creative combinations with one another, to empower workers to design and enforce the safe, healthy workplaces they need.