Another Billionaire Bailout: Private Equity Grabs Working People’s Retirement Savings

In the first week of August, the Trump administration announced a new Executive Order, “Democratizing Access to Alternative Assets for 401(k) Investors.” But there’s nothing about this Order that supports democracy; it’s pure kleptocracy, granting the wealthiest billionaires new opportunities to pick the pockets of working people.

The Executive Order encourages adding private equity funds, as well as other “alternative investments” including cryptocurrency, to individuals’ 401(k) retirement funds. While the Order uses the language of allowing more people to access the “opportunity” to invest in private equity funds, there are very good reasons that these funds have previously been restricted to the ultra-wealthy and institutional investors. Instead, what this Executive Order actually does is bail out billionaires and bankrupt working people’s futures.

Private Equity Funds: Risky, Secretive, Rife with Conflicts of Interest

Private equity has become synonymous with predatory capitalism as these funds have been buying up housing, healthcare facilities, and household names like Red Lobster, Joann Fabrics, or Forever 21, cutting costs, scrapping the business out for parts, and leaving communities in the lurch. Deal after deal in which working people and communities suffer job losses, reduced care, higher costs, all to enrich just a few wealthy investors at the top. Now that they’ve pillaged vast swaths of our economy for their own short-term gains, private equity is coming for the estimated $12-13 trillion that working people in the U.S. have saved in 401(k) funds for their retirement. Private equity bosses are making the pitch that this is ordinary people’s chance to get rich. But it’s actually their latest scheme to socialize their risks while privatizing the profits.

For years, billionaire bankers, private equity firms, and their lobbyists have been calling for a rewrite of the rules that aimed to protect working people’s retirement savings. Those rules, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), establish guidelines to ensure that workers’ retirement funds are managed responsibly. These guidelines mean that most 401(k) retirement accounts for workers invest in bonds and the relatively regulated stock market. Meanwhile, to date, private equity funds have worked by pooling money from ultra-wealthy individuals as well as institutional investors (such as university endowments, pension funds, and sovereign wealth funds).

There are a few key features that distinguish private equity investments from investing in the stock market, a public market.

| Public Markets | Private Markets (including private equity firms) | |

| Who can buy | Anyone with an investment account. | “Accredited” investors: ultra-wealthy people and institutional investors who are better set up to absorb risky investments (Trump’s EO would change this). |

| When you can sell | Stocks in publicly traded companies can be readily bought and sold, generally considered a “liquid” asset. | Investments in private equity firms are generally locked in for 10-12 year period, an “illiquid asset.” |

| Transparency | Companies are required to submit fairly extensive disclosures to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). These publicly available disclosures include financial information as well as strategic plans and assessments of risks to the business. | Few public disclosure requirements; disclosures to investors are also limited. |

| Voting rights | Anyone who owns a voting share can vote in a company’s shareholder meetings. | Investors in PE funds are generally considered limited partners without voting rights in companies (not to be confused with general partners, the PE bosses who are very involved in the companies owned by their funds). |

| Investment value | Stock prices are set by traders buying and selling; prices fluctuate daily and are visible to all online. | Prices are calculated based on complex analysis and calculations made by fund owners. Conflicts of interest are high and investors are expected to do their own due diligence. |

Historically, private equity and other “alternative investments” have been restricted to the ultra-wealthy and institutional investors because they are riskier with fewer disclosures, less liquidity (or access to your money), and a lack of transparency that makes it hard for regular investors to evaluate their investments. Private equity funds also have much higher fees, often 2% of money invested plus 20% of any profits made, compared to the approximately 0.3% fees on the mutual funds of publicly traded stocks and bonds that make up most retirement investment accounts.

Breaking Down the Billionaire Bailout

In the first half of 2025, as the Trump administration’s policies have created chaos and economic instability, the billionaires at the top of private equity firms have found their supply of ready cash drying up. In June, Yale University announced its intention to sell off private equity investments. What had once been pitched as an investment that would pay out higher returns than the stock market no longer looks that way: over the past two years, private equity returns to their institutional investors have been the same or lower than if those investors had invested that money in the stock market. “Do you want to be smart like Yale?” was once the pitch to institutional investors. Now, a New York Times headline asks, “Is Private Equity Overrated?” As institutional investors are getting smart to the private equity scam, private equity funds are looking for a new source of other people’s money to gamble with.

By targeting working people’s 401(k) funds, private equity firms are repeating a pattern that appears across their rapacious acquisitions: targeting people with few other options or information. Across the country, private equity firms have bought up subsidized affordable housing, apartment complexes, and mobile home parks – sites where residents have the fewest resources to move or fight back against predatory tactics. By targeting 401(k) funds just as institutional investors may be souring on private equity, the private equity bosses are getting access to a pool of funds held by working people who often have little information or control over their money. Indeed, some of the most common advice given to people about managing a 401(k) account is to contribute early and often, get any employer match available, and leave the money in place. This set-it-and-forget-it advice gives private equity firms exactly what they need: more cash, few questions.

Billionaire bankers and private equity cronies’ investment in the Trump administration has paid off. The budget bill that passed Congress in early July 2025 checked off many items on private equity’s long-standing wishlist of deregulation and tax breaks, making it easier for the billionaires at the top to hoard wealth at the expense of public goods. Now the latest executive order gives billionaires what they’ve been wanting for years: access to the approximately $12-13 trillion that working people have invested in 401(k) accounts for their retirement.

Gambling Away Working People’s Futures

Trump’s Executive Order is just the latest way that corporations have tweaked the rules to push the risk and cost of workers’ retirement off their books and onto working people. 401(k)s and similar retirement plans are a relatively new invention that took off in the 1980s. Before that time, working people would most likely have a pension plan that was a “Defined Benefit” (DB) plan, meaning that employers are responsible for paying out a set amount of money to retired workers. By contrast, 401(k)s are what are called “Defined Contribution” (DC) plans, meaning that an employer’s contributions are set and it’s up to the worker to invest them. In a DB plan, if the money invested on the workers’ behalf doesn’t make as much as expected, the employer is on the hook to make up the difference. But with a 401(k) or other Defined Contribution plan, the risk is on the worker. If the notoriously volatile stock market crashes, they’re on their own.

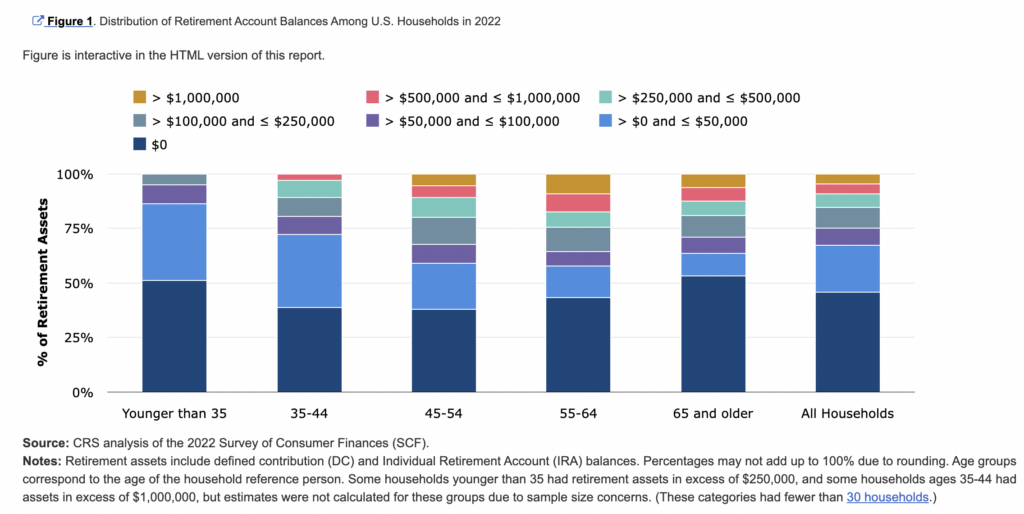

Research has shown that this shift of risk and costs to working people has steadily widened the gap between rich and poor people and exacerbated racial and ethnic disparities. Today, 46% of households in the U.S. have no retirement savings, and an additional 22% have less than $50,000 in assets.

In distressing news, workers are tapping into their 401(k) savings at a record rate. While these funds are supposed to be set aside for retirement, in 2024, 4.8% of account holders tapped into their funds with economic hardship outweighing the stiff penalties incurred for early withdrawals. That number is more than double what it was pre-pandemic.

Taken together, these numbers paint a grim picture. Nearly half of households in the U.S. have no money set aside for retirement, and the ones that do are increasingly needing to access that money to keep their families afloat as housing prices rise and employment becomes more precarious for many. While money invested in stocks is readily available, money invested in private equity funds is typically locked in for the duration of the fund (often 10-12 years). It’s clear why this sort of investment has been the domain of the billionaire class whose yachts, collection of vacation homes, vast investment portfolios, and teams of financial advisors cushion the ups and downs of life and the markets.

Lastly, low-wage workers and the increasing number of people employed in the gig economy often have neither traditional pensions nor 401(k) accounts. Instead, an estimated 40% of older Americans rely solely on Social Security to pay their bills. This publicly administered retirement program is also under threat, with U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent recently bragging that provisions in the latest budget bill are “a backdoor for privatizing Social Security.”

“A Massive Train Wreck”: Experts Predict the Consequences of Private Equity in 401(k)s

Private equity bosses have managed to wring billions of dollars out of communities across the U.S. and the globe using elaborate financial schemes. They’ve secretly rewritten what most people understood as the rules of the economy, driving businesses that appeared to be doing good sales into bankruptcy by saddling them with debt and milking them dry with exorbitant fees. Private equity firms have done this in part by taking advantage of low interest rates and a ready supply of other people’s money. Now that the financial tides have turned and savvy institutional investors may be souring on private equity, these billionaires are turning to regular people’s hard-earned retirement savings to bail them out – and get enough cash to keep buying up and bankrupting community hospitals, businesses, and homes. “The result will be a massive train wreck where many people are seriously hurt,” Knut Rostad of the nonprofit Institute for the Fiduciary Standard told NBC News. “Their retirement accounts will be annihilated.”

Trump’s executive order gave the Department of Labor (DOL) 180 days to act and revise ERISA guidance. Just a week after the order, the DOL has already rescinded Biden-era guidance that cautioned against including private equity funds in individuals’ 401(k) plans due to their high fees and expenses, conflicts of interest, and lack of transparency in how the assets are valued.The next step is for the current DOL to issue its own guidance. There is not a hard law that excludes private equity from 401(k) funds; instead, what’s at stake is how exactly a company’s fiduciary responsibilities are defined, which is to say, their risk of being sued if and when the “massive train wreck” predicted by experts happens. “It will be on the Secretary of Labor to understand how we can stifle that litigation to allow for innovation to occur,” Dan Cahill of Partners Group, the Swiss-based private equity firm that has led lobbying efforts for these changes for a decade, told Forbes.

While the DOL has the final say in defining that fiduciary responsibility and risk, the response to the Executive Order is very clear: economists, personal finance experts, and industry watchdogs are all in agreement. In the words of one columnist, “Workers do not need private equity in their 401(k)s.” On the other side, private equity firms, billionaire bankers, and their lobbyists can’t seem to suppress their gloating enthusiasm as the Trump administration bails out their profits on the backs of working people.